The Chain Across The Golden Horn

By Paul Kastenellos

Harbors as well as rivers that lead into a nation’s interior have always been inviting naval targets. A fleet bottled up in port as the US Navy was at Pearl harbor is a sitting duck unable to maneuver. French Normandy was handed over to Viking raiders on the promise that they would cease to attack Paris via the Seine. Since the Carthaginians chains have been used to deny entrance to an enemy. In fact as late as World War II antisubmarine nets hung from chains or wire ropes and supported by floats were a common and effective defense. In ancient and medieval times they were used to protect the harbors at Famagusta, Antalya, Rhodes and elsewhere. Even much later a floating chain across the Hudson River at West Point denied to the British their intent to split the northern from the southern colonies during the American Revolution. But perhaps the most famous was the chain across the Golden Horn at Constantinople. That great city, the jewel of Christendom from its founding in 330 CE (AD) until its loss in 1453, was built upon a peninsula jutting from the European side of the Bosphorus and protected on three sides by water. The fourth side was secured by its great triple walls which converted what nature had made its most vulnerable side into its most formidable defense.

Two of the three remaining sides were relatively uninviting to an attacking force. Land walls protected all sides facing the water but an attack along the Sea of Marmara or the Bosphorus would have been particularly hazardous. It could not long be supported whereas the Golden Horn was a calm and narrow environment and its relatively unprotected northern shore, the Genoise suburb of Galata, would make a base from which, once secured, an attacker could continually mount attacks on the city itself.

Now a chain might seem an insubstantial obstacle. Merely loose or cut it at one of its mooring points or smash into it with a ship. But harbor chains were kept from dropping to the sea floor by wooden floats or barrels which also gave them flexibility. The ends were secured within fortress walls and anyone attacking these, even at night, would surely come under a fusillade of arrows, spears, and rocks. Still, if attacking ships could not shatter the iron links or an amphibious raid loose the ends, surely a suicide crew under fleet protection might hack away at the chain’s floats with axes so that it would drop to the bottom silt. That scenario assumes however that the opposite side of the chain was not defended by dromon battleships spraying Greek fire into the attackers’ faces.

Much is made of these local defenses of Constantinople. What is not so much emphasized is the difficulty in even approaching them. The cities along the Bosphorus, the Dardanelles, and the Sea of Marmara were usually in Byzantine hands until the onslaught of the Ottoman Turks. The only enemies likely to reach it by sea were Bulgars and Russ coming south from the Black Sea or Arabs coming North from the Aegean. So long as the defenses at Anydos near modern Canakale and Yoros where the Bosphorus exits the Black Sea held, Constantinople could only be attacked on the landward side protected by those well-famed walls.

The best way to defend any place is to engage the enemy far from it. The best way to defend Constantinople from an Arab naval attack would have been to control the Dardanelles and the choke point at Abydos. That port city seems to never have been directly threatened by an Arab fleet. Rather it had to be taken by arduous fighting across Asia Minor. Once in Turkish hands it became a narrow crossing point to Gallipoli instead of a block to invasion by sea. Can it not be argued that the strength of Byzantine naval forces and fortress-mounted ballistic weaponry together with the difficulty of sailing upstream against a strong current from the Black Sea had made a naval attack at that point so obviously a bad idea that Abydos was as important to the defense of Constantinople as the city’s triple walls?

The literature about the chain generally assumes some rigidity in it; yet a moment’s visualization shows that a fairly inflexible chain would have been a weaker defense than one that bobbed about. A relatively loose chain with regular buoys to support it would entangle any ramming ship but not necessarily break. Likewise it would bob about under the impact of axes. A barrier of large stout oak or other hardwood logs connected by relatively short lengths of chain – which seems to be what Leo III emplaced to forestall an Arab assault in 717 – would be a more formidable obstacle both to galleys ramming at their top speed of about five miles per hour or to men with axes.

The Golden Horn was only forcefully taken three times: by the Russ, by the knights of the robber fourth “crusade,” and by Mehmet II – known as the conqueror – who bypassed the chain and is reported to have seized the Horn with warships dragged unopposed in a single night across a hill of Galatea – a patently impossible feat but not one which we shall challenge here. What cannot be known is how often the chain’s very existence discouraged attack. A negative cannot be proven. Likewise we cannot know if there was more than one chain over the centuries. The first description is by Theophanes Confessor but his verbiage seems to assume the existence of a chain before the Arab siege of 717. There is considerable dispute among experts as to how many chains there may have been and their construction. Comer Plummer basing an essay on the research of Byron Tsangadas writes that the “Golden Horn posed a certain challenge for the Byzantine engineers, since the five miles of sea walls in that area were comparatively weak and the calm waters there could provide a safe anchorage to an enemy fleet. Emperor Leo III provided the tactical solution in the form of the famous barrier chain. Made of giant wooden links that were joined by immense nails and heavy iron shackles, the chain could be deployed in an emergency by means of a ship hauling it across the Golden Horn from the Kentenarion Tower in the south to the Castle of Galata on the north bank. Securely anchored on both ends, with its length guarded by Byzantine warships at anchor in the harbor, the great chain was a formidable obstacle and a vital element of the city’s defenses.” The tenth century chronicler Leo the Deacon mentions the two ends of the chain being “fastened to enormous logs” and secured at the tower of Kentenarion on the side of Constantinople and the tower of Kastellion on the northern shore of the Golden Horn as part of the preparations of the Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas against a possible Russian assault.

This description does not jibe well with the chain that defended the city against Mehmet in 1453 and which is probably the same iron chain sections of which are preserved in various Istanbul museums. The links of the 1453 chain were apparently cast in the same or matching molds but then hammered as wrought iron. I submit that instead of the usually accepted floats supporting a chain the entire distance from Topkapi to Galatia, the many sections of seven links each were linked nose to tail to long and thick logs, except, of course, where the chain exited the water to be fixed at towers. The chain made by the engineer Bartalomeo Soligo before Mehmet’s siege may well have been made with old metal and new wood.

Of course the chain would have been secured to strong fortifications at both ends, The northern end is accepted as having terminated in a small fort at the eastern end of Galata which would have been Byzantine territory at the time it was built though that suburb – but not the fort itself later was ceded to Genoise merchant enterprises. Today it is known as the Yeralti Cami or underground mosque since the supporting basement substructure was at one time used as a place of worship. Unfortunately this building has been so often built over and used for so many purposes that if a ring at the chain’s end secured it there the spot, even if intact, is buried within other structures.

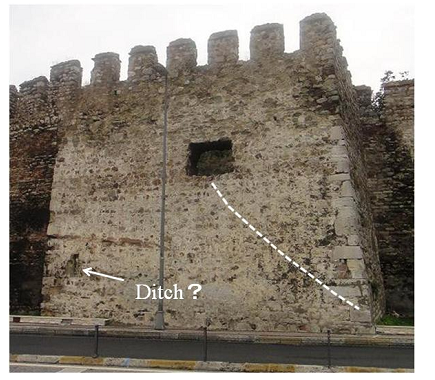

As to the southern terminus, Junichi and Yoshihiko Takeno argue that the southern terminus of the chain was at a tower roughly east of Topkapi palace and somewhat south of the usually accepted southern point. They support this theory by noting that the tower’s construction varies from that of other towers and by citing marks on its walls where the chain might have been dragged. Importantly to their argument is the existence of a rather large opening in the tower. According to their theory the chain would have been pulled a distance along the shore before entering the water where it would be buoyed by floats (or logs). From there its weight would be negligible. Although the chain may have been pulled into the tower by a capstan they theorize that it also could have been drawn by a waterwheel using water from the Basilica Cistern, the Yerebatan Sarnici, nearby Hagia Sophia cathedral.

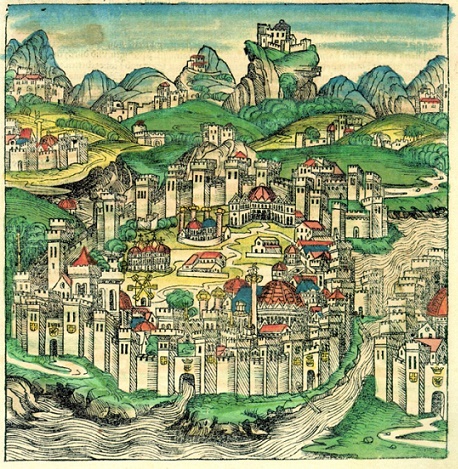

And what exactly happened to the chain after the Turkish conquest? The Nuremberg Chronicle shows the chain extant in 1493, forty years after the conquest. But of course that may merely indicate an historical assumption

According to Ugur Genc who has made a detailed study of the sections, after the conquest the chain was stored intact for a time in the church of St Irene with sections eventually given to four (or five) museums in the city. Indeed it would be unlikely that it was divided immediately after the conquest since a western counteroffensive would have been expected and St. Irene’s was being used as a military storehouse. In time as naval ordnance improved its original purpose became moot and it became a mere “heap of iron” of no worth except to commemorate the siege by Mehmet.

The links in the museums are approximately two foot long and connected every seven links by hook-like members. In actual use these would not have been connected together but either to floating supports or, I submit, to long and heavy logs. As noted above, the latter would have provided a substantial part of the overall length. What remains may be all the iron there ever was. In fact a better image of the chain might be conjured by terming it a chain-linked boom.

Fascinating as it is to imagine dromons spewing Greek fire at enemies on the opposite side of the chain, whatever the details of its construction the existence of both the chain and liquid fire (as the Byzantines called it) discouraged such attacks on the Horn. Yet some stories, almost certainly fictitious, are too fun to not repeat. The eleventh century Viking King Harold Hardrade is said to have crossed the chain by having his rowers advance his ship with all speed while other crewmen holding casks of water placed themselves at the stern so as to raise the bow above the chain then ran forward to tip it over. A silly tale perhaps but indicative of what a Viking crew might boast that their long ship could do.

However the real history of the Golden Horn is nearly as fascinating. In 941 the Rus’ attacked Constantinople with hundreds of small boats while the Byzantine army and navy were away at war with the Arabs. There seems not to have been a battle at the chain but instead the emperor armed with Greek fire fifteen old hulks which had been scheduled for the breakers. These derelicts allowed the Rus’ boats to surround them before opening fire. It was a slaughter with many Rus’ preferring to drown rather than burn. Captives were beheaded.

In 821 the ships of the rebel Thomas of Gaziura – inaccurately called the slav – bypassed the chain and fought a number of battles with the fleet of the emperor Michael II within the Golden Horn and on the Sea of Marmara. A Saracen attack in 717 was in part frustrated by the chain of Leo III described above. The Arab fleet after being soundly defeated by fire spitting dromons under the city walls in the Bosphorus tried to assault the city from the Horn but were denied entry by the chain, no doubt supported by warships.

Only twice was the chain actually breached. In 1203 knights of the fourth (robber) “crusade” managed to seize the Galata tower while Venetian rams attacked the chain itself. Once the chain had been neutralized their fleet was able to enter the horn and it was from there that a successful attack on the city walls was made and the queen of cities fell and was sacked, never to fully recover.

Only twice was the chain actually breached. In 1203 knights of the fourth (robber) “crusade” managed to seize the Galata tower while Venetian rams attacked the chain itself. Once the chain had been neutralized their fleet was able to enter the horn and it was from there that a successful attack on the city walls was made and the queen of cities fell and was sacked, never to fully recover.

Weak and denuded of its riches by the “Franks” the wreckage of the still proud city was eventually seized by remnants of the empire in Trebezond on the Black Sea who entered via an unguarded gate fifty eight years after its fall. The city and factious remnants of the empire continued to hobble along for nearly another two hundred years with each despotate, principality, and duchy generally at war with each other and often cooperating with their more powerful Turkish neighbors. In 1453 Mehmet II decided that enough was enough. Constantinople had long since been completely surrounded by his empire which stretched to the Balkans with this bit of Christianity tenuously holding out like a thumb in his Muslim eye. The story of the fall of Constantinople is well known and will not be repeated here except to note how well the chain still worked. Two attempts to break it by ramming failed and it was once opened for a relief ship then quickly closed again. The chain could do what it was designed to do but Mehmet was meanwhile preparing an oiled wooden road and carts and mules and with these he allegedly drew eighty of his smaller galleys over a two hundred foot high hill at Galata and descended into the Horn. Although the defense of the city had been aided by some Venetians and Genoise other Genoise merchants in Galata, seeing the writing on the wall, did nothing to inhibit Mehmet’s ships being transported or even warn the emperor. There was a naval battle. The Byzantines lost. Now the city’s massively outnumbered defenders had to hold the walls along the Golden Horn as well as the land walls. The enemy camped in Galata and attacked at will. At last on May 29, 1453 the Theodosian triple wall was pierced at Blacarnae and the long drawn out death agonies of the empire were at an end. As noted above, the great chain may have been retained for a time but it was never used again and remained for too long just a useless heap of iron until finally taking a place in the city’s museums.

Sat 9 Sep 2017

THE MOST BYZANTINE VILLAGE IN GREECE

Posted by belisarius under Byzantine Essays (edit this)

No Comments

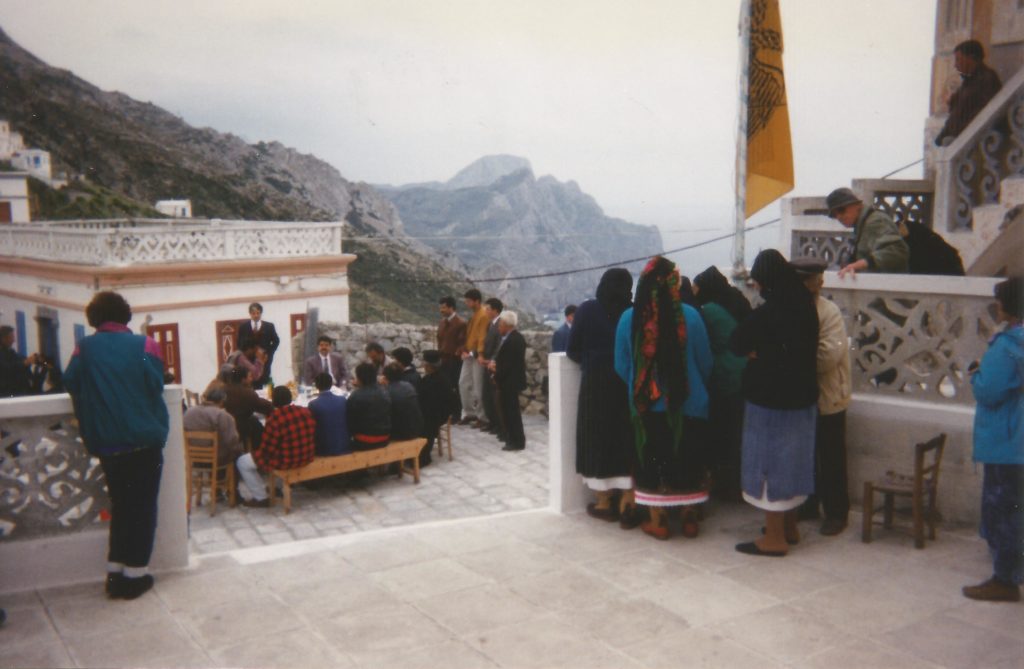

Some twenty years ago my wife and I visited the village of Olymbos on Karpathos in the Dodekanese islands. (Locally known as Elympos.) Our guidebooks had said that it was the most Byzantine of Greek villages and in fact preserved some medieval Greek and even Doric words not used elsewhere. At that time Olymbos or Olympos was still quite off the beaten path – the beaten path from the airport at the south end of the island being possibly the worst maintained road I’ve ever taken. I was happy that a cab driver convinced me not to rent a car. He likely saved our lives and was himself unwilling to drive it at night. The road – which had only been pushed through the rocky and mountainous countryside a decade or so before – was on the side of a cliff, largely unpaved, and it often washed away. There are Youtube videos of it and it seems not to have improved since. En-route to Olymbos our middle aged driver tells us that everyone (every male I presume) in the villages that we passed had worked in either Germany or the USA. At twenty-two his father had picked him a fourteen year old bride. Inheritance had passed through the first daughter on Karpathos, he told us, but today a father tries to provide a house for each girl child.

Olymbos is the female form of the Mt Olympos on which it is built. (There are quite a few peaks with that name.) It is thought to have been founded by refugees fleeing Saracen pirates who regularly attacked their villages in the 7th and 8th centuries. The mountainside is still lined with windmills, some of which still operate. Their horseshoe shape which resembles the towers of a fort was probably intended to deceive pirates. Not much is known about the specific history of the town or island during its Byzantine period but I was told by a local resident that the remains of four actual forts remain on Karpathos. That fact motivated me to write a never published short story about the people there preparing to fend off attackers intent on seizing their children as slaves, for indeed except for sheep there is little else of value on the stony mountains that form Karpathos.

This isolation for years kept the modern world from encroaching and even now the few hundred remaining residents keep alive their Byzantine era music, dances, and costuming – at least at festival times. Many Olympiaites now live in communities on Rhodes and Piraeus but visit their birthplace for festivals. We were there for a traditional Easter service and festival until the Tuesday after Easter when everyone including many ancient ladies seemingly effortlessly make their way along a steep and rocky path down to the cemetery where they distribute and share food – from home made cheeses to candy bars. A list of Olymbos festivals can be found at http://www.visitolympos.com/#xl_xr_page_index.

The Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros Phokas, after ejecting the Saracens who had occupied that part of the Dodekanese, formed the Thema of Crete which included Karpathos. Later it was governed by the Cretan-Venetian Kornaros family until 1537 when the Turkish navy overthrew “Frankish” rule. The distant Turkish rulers allowed the island a rare semi democratic self rule.

Of daily life on Olymbos Constantine Minos and Manolis Makris write that before the introduction of machine made shoes many men were shoemakers or blacksmiths. A unique hand made boot is still made and worn at Olymbos. “Nobody was idle in Olympos, apart from the sick. The living conditions and the environment enforced a certain lifestyle from the early age. Weak people could not live for long in Olympos. One had to have a very good face ‘from one night to the next’ which means from ‘from sunrise to sunset.’ The women were no exception. On the contrary, besides taking care of their children, the women had care of cooking as well, whereas Saturdays were baking and washing days. On Saturdays the men were also busy digging, cutting wood, bee keeping, or repairing their “stivania” (a kind of laced boots) or their tools. Only on Saturday evenings and Sunday mornings were the men free to go to the kafenio where they learnt the news and met other people. The husband and wife in Olympos were two inseparable partners working together against the difficult conditions in order to make a living for themselves and their many – six on average – children. If, on the other hand they were down on their luck, and they had to raise a loan, the man would put his field or house in pledge. If it were necessary to spend the wife’s sovereigns (gold British sterling coins), he would give her his house or field in return.“

Writing about local music and dance, Minos and Makris continue that even today “there are many traditional songs written in fifteen syllable lines calked sirmatika … The songs start very slowly. Somewhere in the middle of the song the beat becomes faster and becomes a crescendo towards the end. The songs are heroic, originating from the Byzantine era, ballads, some are historic songs, some talk about immigration … The exterpore martinades (couplets) are still flourishing.” Some praise and express their wishes to a newly wed couples, to the child who has just been christened… (and) to immigrants who have recently returned from abroad.

Much of this material and more can be found in an on-line article by Constantine Minos, Lecturer at the Aegean University. and his associate the writer Manolis Makris. I also recommend to the reader the photography of Julia Klimi, and quite a number of other photos and excellent videos also available on-line. Many of the videos are narrated in English but there are interviews with the islanders in German and Greek as well.

Vincent O’Reilly (aka: Paul Kastenellos)

The most Byzantine village in Greece

Some twenty years ago my wife and I visited the village of Olymbos on Karpathos in the Dodekanese islands. (Locally known as Elympos.) Our guidebooks had said that it was the most Byzantine of Greek villages and in fact preserved some medieval Greek and even Doric words not used elsewhere. At that time Olymbos or Olympos was still quite off the beaten path – the beaten path from the airport at the south end of the island being possibly the worst maintained road I’ve ever taken. I was happy that a cab driver convinced me not to rent a car. He likely saved our lives and was himself unwilling to drive it at night. The road – which had only been pushed through the rocky and mountainous countryside a decade or so before – was on the side of a cliff, largely unpaved, and it often washed away. There are Youtube videos of it and it seems not to have improved since. En-route to Olymbos our middle aged driver tells us that everyone (every male I presume) in the villages that we passed had worked in either Germany or the USA. At twenty-two his father had picked him a fourteen year old bride. Inheritance had passed through the first daughter on Karpathos, he told us, but today a father tries to provide a house for each girl child.

Olymbos is the female form of the Mt Olympos on which it is built. (There are quite a few peaks with that name.) It is thought to have been founded by refugees fleeing Saracen pirates who regularly attacked their villages in the 7th and 8th centuries. The mountainside is still lined with windmills, some of which still operate. Their horseshoe shape which resembles the towers of a fort was probably intended to deceive pirates. Not much is known about the specific history of the town or island during its Byzantine period but I was told by a local resident that the remains of four actual forts remain on Karpathos. That fact motivated me to write a never published short story about the people there preparing to fend off attackers intent on seizing their children as slaves, for indeed except for sheep there is little else of value on the stony mountains that form Karpathos.

This isolation for years kept the modern world from encroaching and even now the few hundred remaining residents keep alive their Byzantine era music, dances, and costuming – at least at festival times. Many Olympiaites now live in communities on Rhodes and Piraeus but visit their birthplace for festivals. We were there for a traditional Easter service and festival until the Tuesday after Easter when everyone including many ancient ladies seemingly effortlessly make their way along a steep and rocky path down to the cemetery where they distribute and share food – from home made cheeses to candy bars. A list of Olymbos festivals can be found at http://www.visitolympos.com/#xl_xr_page_index.

The Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros Phokas, after ejecting the Saracens who had occupied that part of the Dodekanese, formed the Thema of Crete which included Karpathos. Later it was governed by the Cretan-Venetian Kornaros family until 1537 when the Turkish navy overthrew “Frankish” rule. The distant Turkish rulers allowed the island a rare semi democratic self rule.

Of daily life on Olymbos Constantine Minos and Manolis Makris write that before the introduction of machine made shoes many men were shoemakers or blacksmiths. A unique hand made boot is still made and worn at Olymbos. “Nobody was idle in Olympos, apart from the sick. The living conditions and the environment enforced a certain lifestyle from the early age. Weak people could not live for long in Olympos. One had to have a very good face ‘from one night to the next’ which means from ‘from sunrise to sunset.’ The women were no exception. On the contrary, besides taking care of their children, the women had care of cooking as well, whereas Saturdays were baking and washing days. On Saturdays the men were also busy digging, cutting wood, bee keeping, or repairing their “stivania” (a kind of laced boots) or their tools. Only on Saturday evenings and Sunday mornings were the men free to go to the kafenio where they learnt the news and met other people. The husband and wife in Olympos were two inseparable partners working together against the difficult conditions in order to make a living for themselves and their many – six on average – children. If, on the other hand they were down on their luck, and they had to raise a loan, the man would put his field or house in pledge. If it were necessary to spend the wife’s sovereigns (gold British sterling coins), he would give her his house or field in return.“

Writing about local music and dance, Minos and Makris continue that even today “there are many traditional songs written in fifteen syllable lines calked sirmatika … The songs start very slowly. Somewhere in the middle of the song the beat becomes faster and becomes a crescendo towards the end. The songs are heroic, originating from the Byzantine era, ballads, some are historic songs, some talk about immigration … The exterpore martinades (couplets) are still flourishing.” Some praise and express their wishes to a newly wed couples, to the child who has just been christened… (and) to immigrants who have recently returned from abroad.

Much of this material and more can be found in an on-line article by Constantine Minos, Lecturer at the Aegean University. and his associate the writer Manolis Makris. I also recommend to the reader the photography of Julia Klimi, and quite a number of other photos and excellent videos also available on-line. Many of the videos are narrated in English but there are interviews with the islanders in German and Greek as well.

Vincent O’Reilly (aka: Paul Kastenellos)

apuleiusbooks.com

The first image most people conjure up of Rome is of infantry legions with short swords and rectangular shields marching over the great Roman roads or forming maniples to annihilate some barbarian. But it was Roman naval power which allowed Rome to defeat Carthage in the Punic wars and Rome never forgot it. Rome recognized the Mare Nostrum as the center of the world as they knew it and referred to the states which bordered on the Mediterranean as the circle of the nations. When Constantine the Great founded his Nova Roma on the Bosporus it was because the peninsula on which Byzantium stood controlled the trade route carrying raw materials, fur, and slaves from the Black Sea to and from those producing the finished goods of the Mediterranean. As important, it was also, one might say, a toll gate on the silk road to China, the first step in Europe, safely west of territory disputed with Persia. From Constantinople it was easy either to take ship to any destination among the circle of the nations or to travel overland through Thrace via the Via Egnasia to the Adriatic and thence via a short safe sea voyage to Rome itself and the western empire.

It is tempting to relate the story of Byzantine sea power only in terms of long ago victories and defeats both of which there were many (http://military.wikia.com/wiki/Byzantine_navy) and to discuss endlessly the composition of Greek fire. In Constantine’s time the imperial coastlines extended from the Black Sea in the north, south to Egypt, and from the Holy Land in the east to North Africa and Spain in the west – and, of course all the islands large and small in between, Cyprus, Sicily, and Crete in particular. Rome ruled the waves until the birth of organized Arab piracy. Much later, with the relegation of its naval defenses to the rising Italian city states, the Eastern Empire ever so slowly collapsed. These generalities cover a period of over 1,200 years.

The Romans had to police a vast area of sea usually infested with pirates, but there was also outright war. The most costly loss to the empire was at Cap Bon when the western emperor Anthemius and the eastern emperor Leo II attempted to retake North Africa from the Vandals in 468 AD. The expedition was a disaster. The Vandal king Gaiseric requested a truce of five days in which to prepare his surrender then waited for a satisfactory wind. When it came he sent fireships into the massed Roman vessels which fell into confusion and were destroyed by Vandal galleys. The empire had committed well over a thousand ships and a huge sum, mostly coming from Constantinople. Some 10,000 Roman soldiers and sailors lost their lives. The doom of the Western empire was sealed and the finances of the east severely damaged. It was not until nearly a century later that Belisarius avenged the empire with a far smaller but successful amphibious invasion on the African coast. Later during his second command of Byzantine forces in Goth-held Italy, he effectively used the sea in a campaign of hit and run tactics which prevented the enemy from consolidating their hold on the peninsula, preparing the way for Narses to gain the final victory.

The defense of the Byzantine coasts and the approaches to Constantinople was initially born by one great fleet. Progressively however it was split between several thematic fleets and a central imperial fleet in Constantinople which also formed the core of larger naval expeditions.

In 1937 Henri Pirenne published his famous thesis that it was the triumph of Islam which broke the unity of the Mediterranean world. Historians now generally agree that the division was not so total, yet certainly there was division and there were few Roman flotillas to hunt down pirates who now saw themselves as Jihadists entitled to rob and enslave the infidels of the Mediterranean islands, the Aegean, and even southern Italy. Piracy and war – declared and undeclared – became the norm. Meanwhile Byzantium also had other enemies – rebels, Slavs, and “Franks” – to occupy her navy both inside and outside its borders.

Crete fell to the Muslims in 824 and despite numerous attempts to free it for 140 years the island was a pirate emirate of slavers raiding the islands of the Aegean. Muslim pirates raided as far as Thessaloniki where in 904 they seized 22,000 prisoners – mostly children – who had to be ransomed by the emperor. At about the same time Islamic armies conquered Sicily though the see-saw history of invasion and counter invasion continued with Norman knights rather than Byzantine cataphracts finally settling it. Although the Arabs did build proper war fleets corsairs never ceased piratically raiding the Mediterranean coast for slaves and booty. Even when attempting permanent occupation Arab fleets would have been largely composed of commercial round ships which could transport the beloved horses of their famous light cavalry. The history of Arab-Byzantine naval warfare is long and tedious with victories and defeats for both and with poor Sicily between them and with Normans and Venetians and Genoise always in the mix for good measure.

Byzantine naval forces did pacify the Levant, the Aegean, and the Black Sea. This should have led to an era of peace and safety. Instead the result was naval neglect. According to Michael Psellos when the Rus attacked Constantinople in 1043 only a few derelict warships were available to the defenders. Fortunately for the city those hulks mounted Greek fire siphons with which they burned hundreds of the small Rus boats.

When Alexius I Comnenus assumed his throne in 1081 his navy was in such terrible condition that he was forced to seek Venetian help against the Norman robber baron, Roger Guiscard. For this he granted them wide trading privileges in Constantinople. Meanwhile, however, he began a process of rebuilding that would take his family some eighty years to complete. The see-saw fighting with Arab raiders and actual naval warfare was resumed.

Much of what we know – or think we know – of Byzantine naval tactics is from the emperor Leo VI who wrote a tactica on the subject. John H. Pryor and Elizabet M. Jeffreys suggest, however, that the emperor was an armchair admiral. They cite the difficulties of some of his suggested maneuvers – including the dropping of snakes and scorpions on an enemy vessel, presumably prior to boarding it. We assume he was confident that these patriotic pests would distinguish between their Christian shipmates and the jihadist corsairs.

A buried Byzantine harbor was discovered in Istanbul during the construction of its subway system in the 1990s At about the same time over forty near perfectly preserved wrecks were found under the anoxic waters of the Black Sea. Interesting as they are, so far none seem to have been warships. But while historians and archaeologists anxiously await the finding of a bireme dromon they have had to rely on old frescoes, illuminated manuscripts and occasional literary references, none of which were intended to depict craft with any degree of exactitude. Enter the afore mentioned scholars Pryor and Jeffreys who in 2011 gathered all that we do know or can reasonably surmise into a single scholarly volume, The Age Of The Dromon, which not incidentally punches quite a few holes in previously accepted theories.

Between 1185 and 1204 under the disastrous Angeloi emperors the fleet, together with other state apparatus, was again woefully neglected. By this time Venice and Genoa had gained so much commercial freedom in the capital and the islands of the Mediterranean and Aegean that perhaps it was thought they should be responsible for naval defense. If so it was a shortsighted hope. With the loss of port revenues in Constantinople and the development of the Galata district along western lines on the north shore of the Golden Horn, the East Roman navy again saw a long and now final decline.

The quintessential Byzantine warship is the dromon, a bireme galley with two lanteen sails originally derived from the Roman Liburna which had a single square sail and an integral ram bow. On the dromon two crews of oarsmen formed an ousia of 108 men and instead of a ram it had a spur forward. There was also a slightly larger battleship, the chelandion, which apparently had evolved from a horse transport. Support ships were powered by the wind and could carry cavalry horses as well as supplies for the galleys.

The Dromon did not begin as a bireme. Originally it was only partially decked over and propelled by a single row of soldier-rowers. Today it might be called a cruiser, light and fast for reconnaissance but unsuitable for use in a battle line with the heavies of two world powers duking it out until one side cries uncle. – rather like Admiral Goodenough’s squadron of light cruisers at the battle of Jutland (1916). But by the tenth century the dromon was another ship entirely from what Belisarius had known. It had evolved just as today’s guided missile destroyer bears no resemblance to the torpedo boat-destroyer of 1900. Yet the name remains. The Byzantines had a predilection for using ancient Greek words for contemporary items only remotely resembling the original. Similarly, what the press calls a battleship today is any large surface ship except for aircraft carriers, not the ships-of-the-line-of battle in Lord Nelson’s time nor the steel line-of-battleships of the world wars. Tenth century “dromons” were now fully decked with two levels of fifty rowers each – one per oar. The fifty rowers below were protected from missiles by the decking, the fifty above wore body armor and were further protected by a shield wall on the gunwale. In hand to hand combat they would fight along with marines, officers, and those charged with handling the strong bow-ballistae and Greek Fire. The total compliment of men and marines and officers might be as few as 120 or as many as 160 under the orders of a captain or kentarchoi. Dromons could likely make two approximately 2 knots (2.3 mph) cruising under oars and twice that in short bursts. The sturdy chelandion may have been employed on the horns of the battle line where shock was most useful. Smaller monoreme galeai or monereis had assumed the dromon’s original use as scouts.

Galleys are notoriously bad sailers and there is no reason to believe that dromons were an exception. Long and narrow (roughly 31 meters long by 4.5 meters wide) and with a low freeboard, they’d invite capsizing in anything but calm seas. Nor could they carry much in the way of supplies. Battles had to be fought in calm and confined waters usually employing a crescent formation, and where possible ambush. The fleet commanders (strategoi) operated under orders from the droungarios tou ploimou or first sea lord in Constantinople. The strategos would station his flagship at the battleline’s middle and tempt his enemy to approach while the heavies on the horns of the crescent turned into his wings. The admiral might fain retreat to lure his enemy into advancing. If so the Byzantine horns would attempt a double enveloping. That accomplished (or not), a melee would ensue with the Byzantines hurling flammables from ballistae and attempting to pulverize the opponents oars by smashing down upon them with the long bow mounted spur. No longer did they attempt waterline ramming as in the days of Roman (and Hollywood) battles. As the opposing galleys approached within arrow range there would be a fusillade of missile weapons from marines stationed in the dromon’s “castles” constructed of wood on either side of the ships. Now the intent would be to grapple and board the enemy vessel, particularly if many of its rowers had been killed or injured when their smashed oars were swept against them. Rocks and incendiary grenades were dropped from mastheads or in larger quantity from a crane (gerania) which could be swung over the enemy ship. Weather permitting, as the ships closed preparatory to grappling and boarding all this weaponry might be supplemented by some squirts of what the Byzantines called liquid fire or sticky fire and which we call Greek fire. It could burn on water and not be extinguished except with sand or urine.

So called Greek fire was the empire’s great secret weapon which time and again brought it victory, and even salvation when Rus and Arabs attacked Constantinople itself. Reputedly in was invented in 673 by an engineer from Syria, named Kallinikos..Two things we know about it for sure: No one is certain of the composition, and the system for emitting it is a confusing mistranslation. The Greek word is σίφων or syphon but that simply means a pipe or tube. Why it is translated with the literal English word siphon with its entirely different meaning is baffling. What exactly was the instrument used to project Greek fire? Surely not a siphon as we know one. More likely a tube was attached to a container of the liquid fire and a bellows of some sort for a pump. But this is entirely speculative. The sources do mention a pump but are unclear whether the mixture had to be preheated before it could be ejected and whether or not it ignited by itself when it hit water. I would submit certain thoughts however: It may have contained the typical ingredients of fire weapons of the Roman world (principally thickened oil) but it certainly was sufficiently different as to be a state secret as lauded and guarded as the A-bomb. There may have been more than one version, in fact there probably was; and confusingly, in time western writers popularly referred to any fire weapon, even Chinese, as Greek fire though there be no connection at all to the real thing. The question should be whether it was pumped at the enemy in a continual stream or, as seems probable, some pressure was built up and the liquid released in shorter bursts with more range. At close range a large amount of the sticky slop lying on the sea and probably containing crude oil (which burns on water) would have endangered the Byzantine ship also. Besides, if one wanted to simply set crude oil aflame it is enough to throw a torch into it. I find the term sticky fire a compelling argument for using it in a pinpoint rather than a broad manner.

Again remembering that the composition while the same in general may have been different in detail at different times and places, setting it alight should have been no great task with ships close together. But using it as an infantryman does in a well known illustration would have been terrifying. As a flame thrower in the hands of troops storming a wall from a flying bridge sticky fire would have been as much a terror weapon as the scene of Germans advancing with flame throwers in the film, the Lost battalion. In this case there would necessarily have been a shielded flame or lighter at the nozzle and buckets of water would not have helped any defenders on the receiving end.

Anna Comnena may have been describing the hand held weapon when she wrote of the siege of Sicily and Dyrrhachium in southern Italy: “This fire is made by the following arts. From the pine and certain such evergreen trees inflammable resin is collected. This is rubbed with sulfur and put into tubes of reed, and is blown by men using it with violent and continuous breath. Then in this manner it meets the fire on the tip and catches light and falls like a fiery whirlwind on the faces of the enemies.”

Although Greek fire was not an explosive itself there is mention of thunderous noise which is hard to explain without resorting to some gunpowder like ingredient. Anna does mention sulfur, one of the ingredients of gunpowder. The inability to put it out (or not) would have been even more important at sea than against squirt guns on land. It is amusing to picture dromons going into battle with barrels of urine close at hand to defend against their own primary weapon.

By the late middle ages neither the dromon, nor liquid fire, nor Byzantium’s navy was anything special. The first had been supplanted by the western Gallee; Greek fire and ballistae were being replaced by longer ranged cannon; and the navy which had ruled the sea that washed the circle of the nations was gone, not in some grand climatic battle or even with a sigh.

(apuleiusbooks.com)

BYZANTIUM AND AKSUM

BY PAUL KASTENELLOS

Eric Flint and David Drake in their Belisarius series of alternative / sci-fi histories have the negusa nagast (king of kings) of Aksum (Axume) as a key character. But there is actually very little historical information regarding relations between the East Roman Empire and the kingdom of Aksum on the Red Sea. The result of this dearth of source material is that the importance of Aksum is ignored or given scant attention in histories of Byzantium. This despite that the Persian prophet Mani (c. 216–274 CE) regarded Aksum as third of the four greatest powers of his time after Persia and Rome, with China being the fourth. In fact the Aksum trade route was Rome’s principal supplier of exotic goods from Yemen, sub-Sahara Africa, and India.

At times Aksum’s trading empire extended across most of present day Ethiopia, Sudan, Eritrea, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, and Somalia thus controlling both the east and west coasts of the Red Sea. The capital city – also called Aksum – is located in northern Ethiopia and its caravans would likely have carried the Yemeni grown frankincense and myrrh that according to St. Matthew were brought to the baby Jesus by the magi. They might have carried the gift of gold as well. Aksum’s overland routes carried gold, other minerals, precious stones, and ivory from the African interior via the upper Nile. Aksum controlled the sea routes of East Roman (Syrian) trade with Yemen, India, and possibly so far as China. Sir Mortimer Wheeler, considering the late first century AD sailor’s manual known as the Peripus of the Etythraean Sea, noted in the 1950s that “behind Adulis lay the kingdom of the Axumites (Aksumites), in what is now Ethiopia or Abyssinia, established not long before by immigrants who had been squeezed out of southern Arabia by combined Arab and Parthian pressure. Now, in alliance with Rome, it became an entrepot of African and Eastern trade, particularly as a focus for African ivory, and received a miscellany of imports which included gold and silver plate for their king and iron and muslin from India.” About the same time Lacy O’Leary wrote that “the sea route between India and Alexandria depended upon the safety of the Red Sea which the Romans continued to police until the days of Justinian.”

Around 356 AD, the Roman emperor Constantius II wrote a letter on an ecclesiastical matter to Ezana, king of Aksum. Aksum is also mentioned in the account of the travels of an Arian bishop, Theophilus “the Indian”, who was sent by Constantius to try to convert the Arabian kingdoms. He seems to have visited Aksum as well. The ecclesiastical historian Ruffians, also writing at the end of the fourth century, gives an account of the actual conversion of the country by bishop Frumentius of Tyre. He became the first Abune—a title still given to the head of the Ethiopian Church.

We do know that the Aksumites built great palaces and royal tombs before their conversion to Christianity. Though these are long gone some of the huge obelisks which where built over the tombs remain, incised with images. Many biblical texts were translated from Greek into the Aksum language (Ge’ez) between the fifth and the seventh centuries. the Ezana Stone with an inscription written in the South Arabian Sabaean language, in Ge’ez, and in ancient Greek might be termed the Rosetta Stone of Aksum,

Around the year 380 AD Himyar (in present day Yemen) accepted Judaism whereas Aksum was already Monophysite Christian. An allusion in the Kebra Nagast (Book Of Kings) appears to refer to an alliance between the Aksum ruler Kaleb and the Emperor Justin I (r. 518-527) to strengthen Aksum’s Christian influence in Himyar. There was no doubt also a major element of Aksumite expansion in the plan though the Kebra Nagast is silent about that. Earlier, Justin’s maltreatment of Jews in Byzantine territories had been answered by the ruler of Himyar, Dhu Nuwas, with a persecution of Christian and East Roman merchants in his realm. Kaleb of Aksum attacked Himyar in return. Then Dhu Nuwas initiated a massacre of the major Christian communities of Himyar and Justin offered Kaleb ships with which to attack Himyar again. In the ensuing war Dhu Nuwas was either captured and killed, or committed suicide. The Patriarch of Alexandria appointed a bishop over Himyar, and Kaleb returned to Aksum leaving the Christian Esimiphaeus as viceroy. Esimiphaeus became the effective ruler. A saint of the Ethiopian Church Kaleb is also revered in the Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches. A ruin near Aksum, Enda Kaleb, is said to be his grave.

While Esimiphaeus was viceroy (or king) in Yemen Justinian succeeded Justin on the East Roman throne. He sent an ambassador named Julianus to both Esimiphaeus and Kaleb with a proposal to divert the silk trade from its old route through Persia, via sea and land to Aksum and on to Alexandria; an illuminating account of the embassy has been preserved in the works of Procopius and John Malalas.

(When) Ellesbaas (Kaleb) “was reigning over the Ethiopians, and Esimiphaeus over the Omeritae (Yemeni) the Emperor Justinian sent an ambassador, Julianus, demanding that both nations on account of their community of religion should make common cause with the Romans in the war against the Persians; for he purposed that the Ethiopians, by purchasing (Chinese) silk from India and selling it among the Romans, might themselves gain much money. The Romans would profit in only one way: that they be no longer compelled to pay money to their enemy. (This is the silk of which they are accustomed to make the garments which of old the Greeks called “Medic,” but which at the present time they name ‘Seric’.) … So each king, promising to put this demand into effect, dismissed the ambassador, but neither one of them did the things agreed upon by them. It was impossible for the Ethiopians to buy silk from the Indians as the Persian merchants always locate themselves at the very harbors where the Indian ships first put in (since they inhabit the adjoining country), and are accustomed to buy the whole cargoes. It seemed to the Omeritae a difficult thing also. (They would have) to cross a country which was a desert and which extended so far that a long time was required for the journey across it, and then to go against a people much more warlike than themselves. Later Abramus, (the successor of Esimiphaeus in Yemen) when at length he had established his power most securely, promised the Emperor Justinian many times to invade the land of Persia, but only once began the journey and then straightway turned back. Such then were the relations which the Romans had with the Ethiopians and the Omeritae (so far as the silk trade was concerned.”)

Another ambassador of Justinian was Nonnosus who according to Gibbon “declined the shorter, but more dangerous, road, through the sandy deserts of Nubia; ascended the Nile, embarked on the Red Sea, and safely landed at the African port of Adulis. From Adulis to the royal city of Axume (Aksum) is no more than fifty leagues in a direct line; but the winding passes of the mountains detained the ambassador fifteen days; and as he traversed the forests, he saw, and vaguely computed, about five thousand wild elephants. The capital, according to his report, was large and populous; and the village of Axume is still conspicuous by the regal coronations, by the ruins of a Christian temple, and by sixteen or seventeen obelisks inscribed with Grecian characters.”

The climatic extremes or differences were also noted by Nonnosus: “The climate and its successive changes between Aue and Aksum should be mentioned. It offers extreme contrasts of winter and summer. In fact, when the sun traverses Cancer, Leo and Virgo it is, as far as Aue, just as with us, summer and the dry weather reigns without cease in the air; but from Aue to Aksum and the rest of Ethiopia a rough winter reigns. It does not rage all day, but begins at midday everywhere; it fills the air with clouds and inundates the land with violent storms. It is at this moment that the Nile in flood spreads over Egypt, making a sea of it and irrigating its soil. But, when the sun crosses Capricorn, Aquarius and Pisces, inversely, the sky, from the Adulitae to Aue, inundates the land with showers, and for those who live between Aue and Aksum and in all the rest of Ethiopia, it is summer and the land offers them its splendors.”

Aksum had reached its last period of glory during Kaleb’s reign. Legends were inscribed in the Ge’ez language, coins were minted, and art and architecture flourished. Aksum controlled traffic on the Red Sea, as well as much of the Indian Ocean and only Aksumites were permitted to sail ships to the Far East.

Santa Maria in Trivio though much modified in the Renaissance retains its dedication by Belisarius.

DIGENES AKRITES

By: Paul Kastenellos

Digenes (not Diogenes) Akrites has been described as a chanson de geste which it is not. It has been forced into the literary genre of heroic literature where it doesn’t quite fit thought there is some of the bluster one expects in heroic literature. When the hero asks his father’s permission to fight wild animals his father discourages him:

But the time is not come for beast-fighting;

The war with beasts is very terrible,

You are a twelve-year-old, a child twice six,

Wholly unfit to battle with the beasts

‘If when grown up I do my deeds, father,

What good is that to me? So all men do.

I want fame now, to illustrate my line,

So his relatives stand aside and let him fight the beasts alone. There was no kid coddling on the Anatolian frontier. He kills two bears and a deer with his bare hands. But that was not enough for the poet.

As thus they spoke, his father and his uncles,

A lion huge came from the withy-bed,

And quickly they turned round to see the boy,

Beheld him in the marsh dragging the beasts.

In his right hand dragging the bears he had killed,

And with no sword he ran to meet the lion.

His uncle said to him: ‘Take up your sword,

This is no deer for you to tear in two.”

The youth at once spoke such a word as this:

‘My uncle and my master, God is well able

To give him, like the other, into my hands.’

Snatching his sword he moved towards the beast,

And when he had come near out sprang the lion,

And brandishing his tail he lashed his sides,

But I get ahead of myself. Digenes Akrites is actually two stories or rather several lumped into two parts. The first is the romantic tale of how his father, an emir from Syria, after raiding “Romania” – killing and enslaving many there – takes as a captive Eirene, the beautiful daughter of the local general who happened to be away at the time. The text makes plain that the general had been exiled from Constantinople to his rural estates in Anatolia where he and his family could be useful policing the frontier against Arab raiders and highwaymen. Eirene’s brothers pursue the emir to his camp.

Our father is descended from the Kinnamades;

Our mother a Doukas, of Constantine’s family;

Twelve generals our cousins and our uncles.

Of such descend we all with our own sister.

Our father banished for some foolishness

Which certain slanderers contrived for him,

The girl’s brothers try either to buy her from the emir or fight for her but to no avail as the emir is besotted by Eirene who still remains a virgin. He speaks to the brothers:

If you deign have me as your sister’s husband,

For the sweet beauty of your own dear sister

I will become a Christian in Romania.

And, listen to the truth, by the great Prophet,

She never kissed me, never spoke to me.

Come then into my tent: see whom you seek.’

Not only does the emir readily move his tribesmen to Romania and convert and marry Eirene, when his mother complains by letter of how he has defamed his family and religion by lusting after a pig-eater he briefly returns to Syria where he converts his mom and whole family to Christianity by simply reciting the Nicene creed and some New Testament quotes. The poet rather humorously describes the emir’s return to Eirene:

When suddenly she saw him coming up

She sorely fainted in a wonderstroke,

And having wound her arms about his neck

She hung there speechless, nor let fall her tears.

Likewise the Emir became as one possessed,

Clasping the girl, holding her on his breast,

So they remained entwined for many hours;

And had not the General’s wife thrown water on them

They had straight fallen fainting to the ground.

(Love beyond measure often breeds such things,

And overpassing joy leads on to death,

Even as they too were nigh to suffer it.)

And hardly were they able to sever them;

For the Emir was kissing the girl’s eyes,

Embracing her, and asking with delight:

‘How are you, sweet my light, my pretty lamb,

How are you, dearest soul, my consolation,

Most pretty dove, and my most lovely tree

With your own flower, (Basil) my beloved son?

Digenes Akrites is a bunch of highly romantic folk tales with a theme. The problem with writing down folk tales is that they become set as in stone. Cinderella as written down by the brothers Grimm is certainly a lovely story but only one version of what circulated mother-to-daughter in earlier years. Until the twentieth century Akritic literature was also passed down orally in Greece and Greek Cyprus. Presumably it was from this rich tradition that the tale of the twice born Digenes Akrites – Basil the huntsman – derives.

But if Basil is the hero’s name, what is with this Digenes? Digenes Akrites translates as two-blood border lord – two bloods referring to his mixed Arab and Byzantine parentage. The title border lord or borderer (akrites) describes his life’s work: protecting the Byzantine frontier not only against Arab raiders like his dad had been but also thieves and highwaymen. Otherwise he is known as Basil the huntsman.

What makes this fairy tale of romance and bad guys and even a dragon so important to academic studies is that it is so entirely different from the usual Byzantine literature of the capital. It came out of the boonies of Cappadocia and the writing does not constantly refer back to classical models. The setting is the Asian frontier in the tenth century or thereabouts but since the earliest version was written down some two hundred years later it reflects the situation of that day. In fact it is a piece of nostalgia for a lost time of Byzantine greatness before the defeat at Manzikirk, never to be fully regained. How much of the text as we have it reflects oral tradition, and how much of later Akritic literature is modeled upon the epic is a matter to be discussed by scholars.

Unlike court literature it is not particularly religious and what religion there is in the tale are set pieces, as with the quick persuasion of the emir’s family noted above; a familiar if boring style of Orthodox hagiography apparently set within a paradigm influenced by the Pauletian heresy. That, however, is irrelevant to the non specialist. In Constantinople everything was viewed through the prism of an autocratic state where the basilius was also the temporal head of the church, one who often viewed himself as a theologian. Digenes Akrites is a romance set on the frontier where the hero’s nearest neighbors and sometimes relatives are Muslim while the enemies he defeats are as likely as not Christian bandits and rustlers. In this Digenes reminds one of the Spanish hero, El Cid, also a border lord. Both heroes are from families of the “Great” who while acknowledging the divine overlordship of king or emperor, are in practice so independent that Digenes can set security conditions for the emperor to visit him. One is put in mind of the English maxim: “a man’s home is his castle” as the king’s authority stops at a nobleman’s fortress.

But one should not overemphasize the heroic element. Homer’s Odyssey is an heroic tale. Penelope’s main virtue is keeping Odysseus’ sheep out of the clutching paws of her suitors. Digenes falls in love with Evdokia at first sight and she with him. The scene cannot but put one in mind of Juliet on her balcony.

When that she saw the youth, as I am telling,

Her heart was fired, she would not live on earth;

Pain kindled in her, as is natural;

Beauty is very sharp, its arrow wounds,

And through the very eyes reaches the soul.

She wanted from the youth to lift her eyes,

Yet wanting not from beauty to be parted,

Plainly defeated drew them there again;

And said to her Nurse quietly in her ear:

‘Look out, dear Nurse, and see a sweet young man,

Look at his wondrous beauty and strange stature.

If but my lord took him for son-in-law –

He would have, believe me, one like no one else.’

So she stayed watching the boy from the opening.

The youth through the embrasure saw the Girl,

And gazing on her, forward made no step,

Amazement took him, trembling took his heart;

He urged his charger, drew near to the Girl,

And to her quietly spoke words like these:

‘Acquaint me, maid, if you have me in mind,

If you much wish I should take you for wife;

If elsewhere be your mind, I’ll not entreat you.’

And the Girl thereon did entreat her nurse,

‘Go down, good nurse, and say you to the boy,

“Be sure, God’s name, you are come into my soul;

Digenes woos her by playing on a lute:

Then rising thence he went up to his room,

He fetched his boots, and then he took his lute,

First with his hands alone the strings vibrated

(Well was he trained in instruments of music)

And having tuned he struck it murmuring:

‘Who loves near by shall not be short of sleep,

Who loves afar let him not waste his nights:

Far is my love and quickly let me go,

That I hurt not the soul that wakes for me.’

The sun was setting and the moon came up

When he rode out alone holding his lute.

The black was swift, the moon was like the day,

With the dawn he came up to the Girl’s pavilion

And low down leaning out (she) says to the boy:

‘I scolded you, my pet, you were so late,

Shall always scold if you are slack and slow,

And lute-playing, as if you don’t know where you are,

Dear, if my father hear and do you harm,

And you die for me

When Evdokia’s father indeed separates the two they elope. When pursued Digenes single handedly defeats the general’s entire army of retainers. His martial prowess is not the important thing however, but how each risks everything for the other, Evdokia even accompanying her husband in his adventures. There is no monkish piety in their story but lots of lust. Christianized lust for each other, but lust none the less at least by the standards of the Orthodox church of the day. In Digenes Akrites there is none of the concern for humility, piety, and the poor that is familiar in Constantinoplean fare but earthy romance, manly virtue, and description of the rich life of the Anatolian aristocracy.

He straightway changed, put on a Roman dress,

A tabard wonderful, sprinkled with gold,

Violet, white, and thick purple, griffin-broidered,

A turban gold-inscribed, precious and white;

Thin singlets he put on to cool himself,

The upper one was red with golden hems,

And all the hems of it were fused with pearls,

The neck was filled with southernwood and musk,

And distinct pearls it had instead of buttons,

The buttonholes were twisted with pure gold;

He wore fine leggings with griffins embellished,

His spurs were plaited round with precious stones,

And on the gold work there were carbuncles.

I would if I could pass over a disturbing element, the affair of Basil and Maximo. Every hero must have a weakness however and for Digenes it is the warrior-maid Maximo, of Amazonian descent, whom he twice defeats in battle, twice spares, is unfaithful with, and than kills out of guilt

Straight mounting horse he went to Maximo.

She was descended from Amazon women,

King Alexander brought from the Brahmanes.

Great was the strength she had from her forebears,

Finding in war her life and her delight.

Maximo appeared in the field alone.

She sat upon a black a noble mare,

Wearing a tabard, all of yellow silk

And green her turban was, sprinkled with gold,

She bore a shield painted with eagle’s wings,

An Arab spear, and girdled with a sword.

They fight. She loses and expects to be slain. She offers her body to the hero.

“You die not, Maximo,” I said to her,

“But it cannot be for me to make you wife.

I have a lawful wife noble and fair,

Whose love I will never bear to set aside

Alas his resolve melts when she

Threw off her tabard, for the heat was great.

Maximo’s tunic was like gossamer,

Which as a mirror all her limbs displayed,

And her small paps just peeping from her breast.

My soul was wounded, she was beautiful

Maximo lighted up my love the more

Shooting upon my hearing sweetest words,

And she was young and fair, lovely and virgin,

Reason was conquered by profane desire;

His wife is not deceived. But she is forgiving.

What stings me is Maximo’s daring delay;

What you were doing with her I know not;

But there is surely God knows what is hidden,

And will forgive this sin of yours, my friend;

But see, young man, you do this not again

Now this much may be said for Digenes. A Homeric hero would have shrugged off the dalliance. A simple warrior might accept it is loot. But Digenes is Christian even if his reaction to his sin makes but little sense to us today. He feels guilt. Though he had twice spared Maximo in battle, for his shame he now kills her. A Freudian might see a demonic dragon which Digenes slays in another chapter as his phallic double. In killing that monster the guilty hero may be symbolically castrating himself for this murder of his seductress. However it is hard for me to believe that some medieval poet thought it out so explicitly. As likely, as it has been suggested, the slaying of Maximo was somewhere inserted into the narrative to eliminate a developing and inconvenient love triangle. That works too.

Many a hero dies in some glorious but hopeless cause. So too our hero – sort of. He and Evdokia retire to an estate which he builds on the banks of the Euphrates and there he dies (In some later versions wrestling with death himself.) content that he has served the empire and his legacy well. Digenes’ single infidelity aside, the love between Basil and Evdokia is strong even to death. He kills but not needlessly, or as revenge, or to impose Christianity on peaceful Muslim neighbors. One can easily imagine a crowd of villagers gathered in some Cypriot town to hear the familiar tale from a visiting troubadour just as the sun sets and the wine flows in rivers like the romance of the poem itself. Evdokia prays over her dying husband:

In loving-kindness pity me in exile,

Have mercy on my loneliness, raise him up.

If not, O God who can do all, command

Me die before him and give up my soul,

Let me not see him voiceless, stretched out dead,

See his fair hands that learned to be so brave

Clasped crosswise, and remaining motionless,

His eyes covered over, and his feet wrapped up:

Allow me not to see such great affliction,

O God my maker, who canst do all things.’

Thus the Girl with much contrition of heart

Having prayed, turned to see the Borderer,

Beheld him speechless, yielding up his soul;

And not bearing the pain of boundless grief

From measureless and great despondence falling

On him in sympathy the Girl expired.

Never had she had knowledge of affliction,’

And therefore was not able to endure it.

The hero seeing, and feeling with his hand,

For he was living still by God’s compassion,

Having beheld her dying suddenly,

Said, ‘Glory to Thee, O God, who orderest all,

That my soul bears not pain unbearable,

That she should be alone here and a stranger.’

His hands setting crosswise the noble youth

Gave up his soul to the angels of the Lord;

Illustrious and young both brought to an end

Their souls at once, as if by covenant.

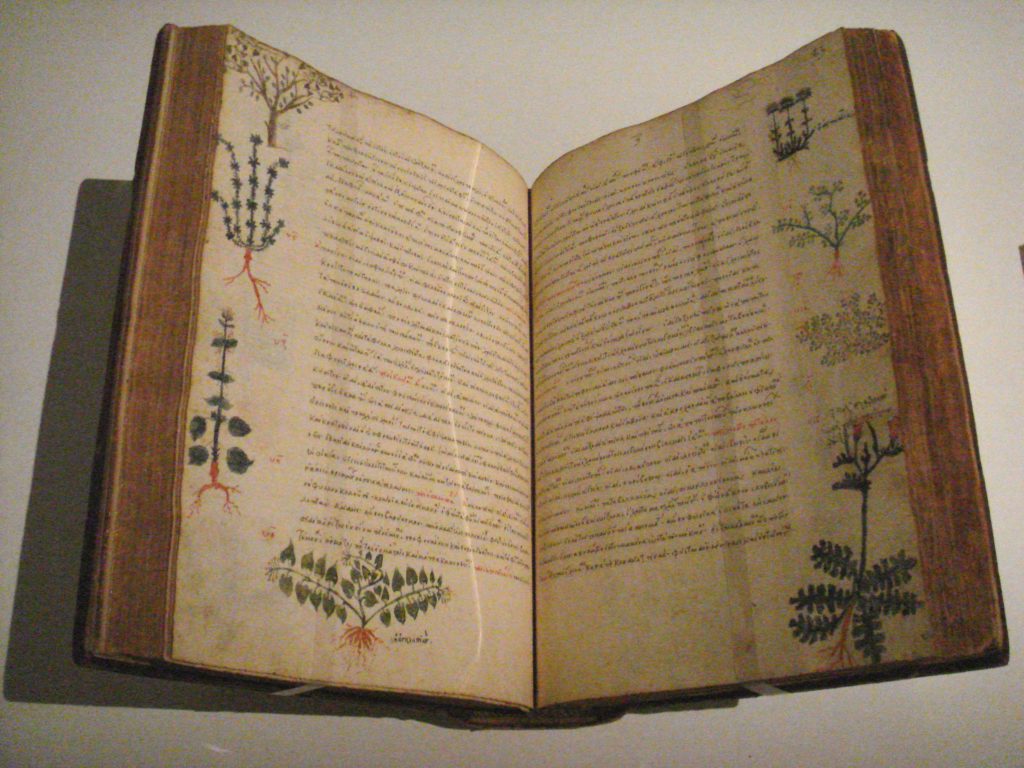

BYZANTINE MEDICINE – WHERE ARE THE BARBER SURGEONS?

By Paul Kastenellos

We do not have a lot of detail about Byzantine medicine nor is what we read in some Byzantine author necessarily true for the entire 1,100 year life of the empire. But both the Emperors Maurice (582-602) and Leo IV (886-912) wrote on medical subjects during the high points of Byzantine history and Manuel I Comnenus himself ministered to the German king Conrad of Hohenstaufen. Of course, as with the “Renaissance man,” it was pretty common for the educated layman of the ancient, medieval, and Arabic worlds to have a scholarly and often self-schooled interest in many disciplines including astronomy, architecture, mathematics, and medicine. Procopius of Caesaria, while not a doctor, gave a fine description of the Justinian plague which hit the empire in 541 AD. He accurately describes how it arrived first in seaports and was not necessarily spread by contact with the victims. As important, he admits his ignorance rather than giving an otherworldly explanation. There is not a word to indicate the wrath of God or the machinations of the devil. Without a knowledge of germ theory he could not recognize the source of infection now known to have been the bite of rat-born fleas. None the less, he is recognized in medical education for accurate observation without preconceived notions.

https://hefenfelth.wordpress.com/2011/07/31/procopius-account-of-the-plague-in-constantinople-542.

Besides these gentlemen scholars, there were the practitioners trained in the schools of medicine who were disciplined by day-by-day medical practice and the need to perform actual surgery. Modern authors are not always helpful, at times exaggerating Byzantine expertise and specialization. With that reservation it can be admitted that though hampered by the dead hands of Galen and Hippocrates the East Roman doctors were – if not very innovative of theory – at least willing to modify theory with practical experience. Medical texts and health manuals throughout the Middle Ages often note the benefits of drinking water, as long as it came from good sources. For example, Paul of Aegina, a 7th-century Byzantine physician, writes “of all things water is of most use in every mode of regimen. It is necessary to know that the best water is devoid of quality as regards taste and smell, is most pleasant to drink, and pure to the sight; and when it passes through the praecordia quickly, one cannot find a better drink.” Surgeons operated successfully on head wounds, haemorrhoids, and hernias, removed tonsils and performed hysterectomies. According to the chronicle of Ioannes Skylitzes surgeons even attempted to separate a dead conjoined twin from his still living brother. (The living twin survived the surgery itself but died only a little later.) The following interesting link gives a thorough description of several methods employed to correct aneurisms:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1078588498801305.

Steven Runciman notes the static nature of Byzantine theory but praises its practicality. Physicians would encourage common sense preventatives while picking and choosing elements from the revered Greek and Roman authors that supported their favored treatments.

Byzantine history is one of nearly constant warfare so there was considerable expertise in treating wounds. The East Roman Army had a medical corp with medics to follow the soldiers into battle, provide first aid, and carry the wounded to MASH units behind the lines. For the cavalry there would be a unit of 8 to 18 men assigned to each detachment of 200 to 400 men. They would follow some 200 feet behind the front line troops in order to bring the badly wounded away from danger. To that end, the saddles of their horses had two ladder-stirrups on the left side, and flasks of water to revive the faint. There were VA hospitals. The emperor Justin II (565-578) founded such an institution in Constantinople as did Alexius Comnenus I (1081-1118) – Alexius placing his own daughter Anna in charge.

Throughout the middle ages it was probably better to have a bone set by an experienced craftsman than by a university educated doctor who might consider surgery below his dignity anyway. As always, village “old wives” ministered with success and certainly monasteries cultivated herbs. Herbals were common and were translated into Arabic and then to Latin and eventually passed into western Europe via Spain. But as noted, the teaching of Hippocrates and Galen had a death grip on medicine throughout Europe so there was not much advance in the theory until Harvey discovered the circulation of the blood. The invention of the microscope showed (or confirmed) the existence of microorganisms. Only then did it become worthy to think outside the box. Byzantium was no exception.

Monastic hospitals for the poor were common throughout the empire, established by an emperor, or by aristocrats and civil servants trying to buy their way into heaven at the end of a less than edifying life. It was usual for monasteries to contain hospital wards for the poor. As elsewhere in medieval Europe these mainly served to let peasants die in clean bed linens just as third world hospices minister to those dying from AIDS today. The first Christian hospital considered to have been built to cure disease rather than just ease the pain and depression of impending death was built by St. Basil the Great of Caesaria in the late fourth century This holy bishop has been credited with convincing other Christians that medical care was a gift from God and not a proscribed paganism.

In the 8th and 9th Centuries true hospitals began to appear in provincial towns as well as cities. Towns were required to have sufficient doctors for their populations. Presumably these were trained at Alexandria or the university of Constantinople. Self taught practitioners like Alexander of Thalles – who produced a medical compendium – used their common sense. Another compendium in seven books by the seventh century practicing physician Paul of Aegina remained in use as a standard textbook for the next eight hundred years.

By the twelfth century Constantinople had two well organized hospitals staffed by medical specialists including women doctors. John II Comnenus established a then modern well organized institution which according to Tamara Talbot Rice was staffed by medical specialists. These contained special wards for various types of diseases and employed systematic methods of treatment. There were ten wards of fifty beds each and there was a dedicated hierarchy including the Chief Physician (archiatroi), professional nurses (hypourgoi) and orderlies (hyperetai). Each qualified male doctor had twelve qualified assistants and eight helpers while the lone woman doctor had eight assistants and two helpers. There were also two “pathologists” and a dispensary to tend outpatients. Talbot Rice also notes that outside the capital everyday practice by state supported doctors – begun by Justinian I – had already somewhat modified ancient theory.

Christianity always played a key role in the building and maintaining of hospitals. Many hospitals were built and maintained by bishops in their respective prefectures. These were nearly always built near or around churches and great importance was laid on the idea of healing through salvation. When medicine, bathing pools, clean air, and cleanliness failed, doctors would ask their patients to pray. This usually involved symbols of saints especially Saints Cosmas and Damien who were the patron saints of medicine and doctors. That said, the Byzantines drew a distinction between miraculous cures, in which everyone believed, and magic. Prayer before icons was encouraged for both its spiritual and psychological benefits. But amulets and spells, while common in the empire, were decried by the church and merely tolerated by doctors.

Anna Comnena emphasized preventive medicine with life style changes, but Andrew Dalby’s Flavours of Byzantium reports extensively on the Hippocratic concern with balancing hot and cold, dry and moist, and the four humors: blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile. In fact we know more about the East Roman obsession with diet and health than we do their actual recipes. He reports that to the Byzantines wheat is the best of all grains and produces healthy blood; that rice is midway between hot and cold and inhibits movement of the bowels but if boiled with seasoning becomes good for the bowels; that broad beans have a high degree of coldness and cause gas while chickpeas which have a high proportion of heat also cause gas, etc. Milk and hen’s eggs produce good humors. Fibrous parts of animals produce phlegm. The meat of oxen and goats produce black bile.

Besides diet other lifestyle recommendations for each month are quoted by Dalby from a Byzantine calendar. For December, which was thought to govern the salty phlegm, one should avoid cabbage and seris (endive or chicory), and eat no goat, deer, or boar. All other meats should be eaten lean, served hot, boiled, and spiced. In December one should also eat fenugreek soup in moderate amounts as well as young green olives in brine and olives in honey vinegar … He should take eight baths using an ointment containing aloes and myrrh washed off with wine and sodium carbonate. … and make love.

Apuleiusbooks.com

Black People In Byzantine Society

http://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2013/08/black-people-in-byzantine-society.html

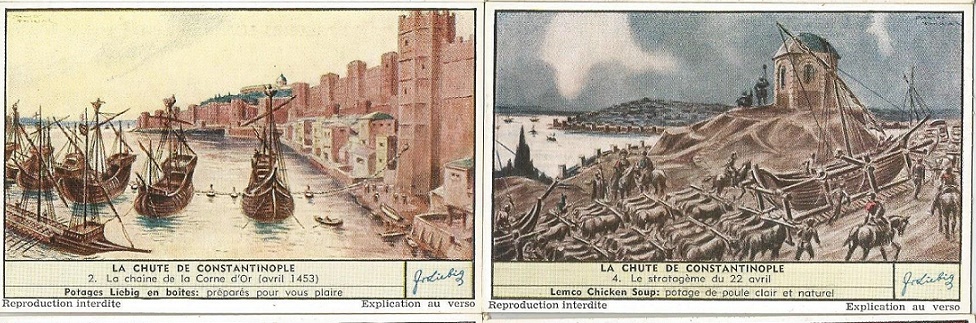

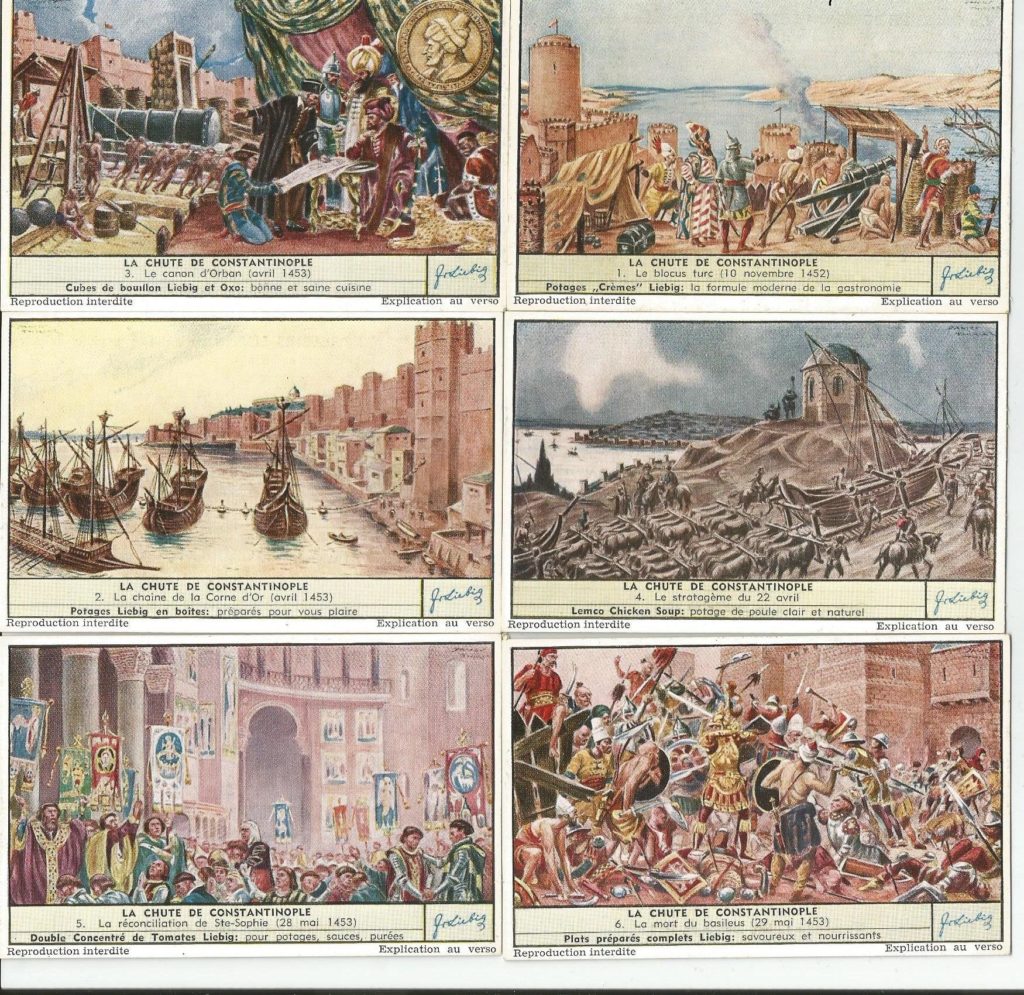

HE FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE DEPICTED ON TRADING CARDS.

ROMAN VS BYZANTINE … AD NAUSEAM.

Arnold Toynbee consistently used the term “East Roman” rather than either “Roman” or “Byzantine.” To him, the Roman Empire was a continuation of Greek / Hellenistic civilization, a point of view shared by the poet Horace who in the first century BC famously wrote that “captive Greece took captive her savage conqueror.” Toynbee divides East and West Roman civilizations as early as the late republic and early principiate, with the East Roman being Hellenistic and the West Roman more in keeping with the traditional image of marching legions and gladiators that in time disappeared as the west declined. Thus he refers to an East Roman culture well before Constantine I divided the administration. Such an East Roman terminology covering an era since before the birth of Christ till the fall of Constantinople may finally satisfy those who feud over whether the later Empire should be called Byzantine or Roman. It was West Roman legions which conquered the world but East Roman cavalry which maintained it throughout the middle ages.

Having made that point I have no desire nor any will to continue the unproductive argument of Byzantine vs Roman terminology. To say Roman to anyone not already immersed in East Roman history and culture is to confuse him only to make a point. In art it would actually be a distortion to speak of Byzantine as medieval Roman. On the other hand, politically the later emperors did rule in an unbroken succession from Caesar Augustus and their laws – even those of Julian the apostate – survived their individual deaths unless canceled by a successor.

Sometimes there is no single “right” way to see something. It was what it was and to each his own. End discussion.

No Responses to “ Byzantine Essays ”